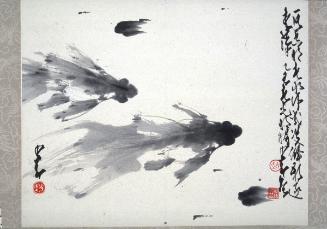

Fish and Waterweed, One of a Pair

Because fish appear to flow in water freely, unburdened by worrisome thoughts, the joy of fish became a popular subject in Chinese art. The idea of joyful fish was closely related to a famous Daoist debate story, which suggests that true understanding can only be acquired intuitively, not through rational study. Here, this subject is amplified by visual puns. The freshwater perch on the left represents nobility and abundance, as its name in Chinese, guiyu, is a homonym for those two words. The carp (liyu) on the right, with upturned lips and piercing eye, exhibits a human-like expression full of humor in pursuit of fame and fortune.

The paintings bear the seals of “Lai’an,” who was probably a late thirteenth-century monk artist. During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Chinese Chan (Zen) art and culture was an important influence in Japan and many Japanese monks brought Chan paintings back to Japan after their religious study in China. While many Chinese Chan artists, such as Liang Kai (ca. 1140–1210) and Muqi (ca. 1210–1269), were neglected in Chinese history, their paintings were recorded and valued in Japan. These Chinese artworks also received scholarly attention in the West, because Japanese collectors and scholars introduced their Western counterparts to the appreciation of this type of Chinese painting in the nineteenth century.

This pair of scrolls may have once flanked a central Buddhist painting as part of a triptych in a temple. Triads consisting of a Buddha image flanked by a pair of bodhisattva images were common in Buddhist art. In Chan versions, fish, gibbons, and other animals sometimes replace bodhisattvas. This substitution would present a shock to many viewers, leading, for some, to an expanded understanding of the inconsequential nature of the world. The very act of repurposing images served as an exercise in meditation, and Japanese monks often borrow secular images to serve in religious contexts (such as Muqi’s Six Persimmons and Chestnuts, a pair possibly cropped from a handscroll). The approach of showing a single object against a spacious background is also characteristic of Chan art.