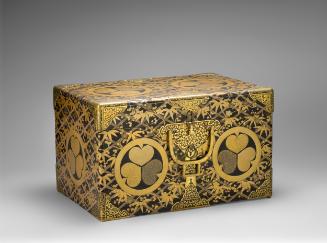

Lidded vessel with design of clouds and phoenixes

戰國秦昭襄王29年(前278年)銘文 彩繪 雲鳳紋漆卮

The covered lacquer vessel is one of the objects in the Asian's collections that can be directly associated with the state of Qin. A little background on the medium: Lacquer is made of the sap of a member of the rhus family, which also contains poison ivy and poison sumac. The sap contains a very high level of urushiol, the chemical in these plants that causes dermatitis on contact.

Raw lacquer is a thick liquid that can be applied as paint or used as a resin, much like the resin for fiberglass. Under the right conditions, it will undergo a chemical change that creates a substance not unlike modern plastic. It is very durable and can withstand exposure to heat and liquids. Urushiol in its raw state is very caustic and only a limited number of stable materials can be used as pigments. For much of the history of lacquer in China these pigments were browns and blacks derived from carbon, and red from cinnabar.

Traditionally the primary centers of lacquer production in China have been along the Yangtze River. Lacquered objects dating from as early as 3000 BCE have been found in archaeological sites in this region; the lacquer has survived in remarkably good condition-the issue is with the cores, which are most often made of wood. Over thousands of years of burial, water invariably penetrates the wood cores which swell and then shrink when they dry. That is the explanation for the wrinkled surface on this piece. In its original form it would have been smooth and shiny with very clearly demarcated designs.

The level of workmanship for this piece is remarkable. The basic core consists of a circular wood base with six very thin and slightly curved pieces of wood making up the walls. The pieces of wood do not appear to have been joined in any way, though it is likely they were glued together, perhaps with lacquer. The wood is covered both inside and out with a single layer of textile. Either the fabric was impregnated with lacquer before it was applied or lacquer was applied directly to it to create a strong and durable object. Close examination indicates an additional layer of lacquer was applied as a filler to smooth out the imperfections in the surface before the finish coats were applied. The finish coats are in black with designs added in red and brown. The interior of the vessel is red.

The three ears on the lid, the handle and the base with three attached legs are cast bronze. Again, there is no clear evidence of mechanical attachments like nails, instead it appears the lacquer serves as an adhesive holding these appendages to the lacquered wood body; there are two holes in each end of the bronze handle, with a groove between them, suggesting that it was tied or wired to something. There is no original lacquer around the handle, so we really don't know for certain if it is even original to this object, though the inlaid decoration matches the other fittings. The elaborate designs on the bronze appear to have been incised and then inlaid with silver. They relate closely to the designs painted in red on the black lacquer surface.

By the time this piece was created, lacquered objects were far more expensive than bronze; vessels like this one were objects of prestige. During the Eastern Zhou dynasty Chu, which occupied the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, was the state best known for lacquer production. A 1956 publication in Chinese indicates that this piece was excavated in Changsha in Hunan province, one of the major centers of Chu culture.

Included in the red lacquer decoration on the lid of this vessel are two designs which can be read as the Chinese character chang (檉's mark. An inscription is incised on the bottom and with it the story of this remarkable piece gets much more complex and challenging. Incising or carving decoration into lacquer objects was just beginning to appear as a decorative strategy in the late Warring States period and the Qin dynasty. In fact, this could be the earliest incised inscription with a date on any surviving Chinese lacquer. The inscription starts with a date: the twenty ninth year, and goes on to state that a dowager queen (tai hou太后

A Chinese scholar has suggested the queen mentioned in the inscription might be the dowager queen Xuan (died 265 BCE) who was a native Chu and mother of King Zhao of Qin who died in 251BCE. If so, the date of the piece would be 278 BCE, making it the earliest surviving example of a Chinese lacquer with a date. Unfortunately, the date does not contain the ruler's name, just the twenty-ninth year. That leaves the actual date open to conjecture; there are several issues with the 278 BCE date.

Qin was not a center of lacquer production until its conquest of Chu territories in 278 BCE. The areas conquered included the Chu capital of Ying, located near the modern city of Jiangling in Hubei province. No doubt centers of lacquer production were also included in the conquered areas. It is possible that the vessel could be spoils of war but that would not explain the style of the calligraphy used in the inscription, the association with a Qin queen, or the fact that it was reported excavated from a tomb in Changsha, which in 278 BCE was still in Chu territory. It seems highly unlikely that the Qin would have been able to put into place the level of bureaucracy suggested in the inscription in the same year they made these conquests.

The piece might have been the property of the dowager queen brought Qin as part of her dowry. Again, that does not explain the style of the calligraphy. Also, there is no evidence in existing Chu documents of the complex bureaucracy associated with the creation of lacquers suggested by the inscription. This is far more typical of the state of Qin. Also, makers' marks are very rare on Chu state lacquers. I do not know of any.

The more likely explanation is the date is not the twenty ninth year of King X, but rather the 29th year of the reign of the First Emperor himself. That would be equivalent to 218 BCE. Such a date would explain all the issues raised above. The problem with this date is the Shiji states that the First Emperor's mother died in the 17th year of his reign. That is equivalent to 230 BCE. An explanation might be found in the reading of the fourth and fifth characters of the inscription. As mentioned above this has been read as tai hou (太后大司