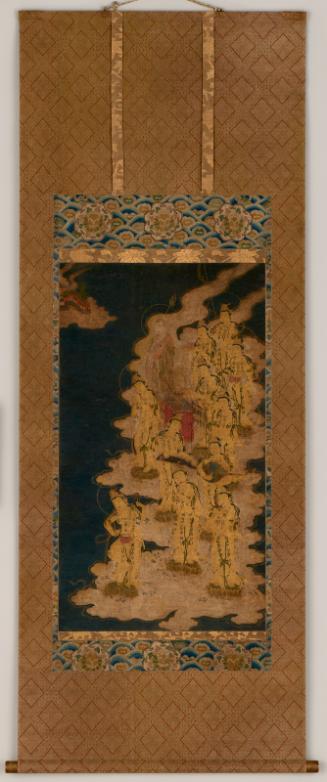

The Monk Yi Xing

Place of OriginJapan

Dateapprox. 1500-1600

PeriodMuromachi period (1392-1573)

CultureJapanese

MaterialsInk and colors on silk

DimensionsH. 29 1/8 in x W. 21 1/8 in, H. 74.0 cm x W. 53.7 cm (image)

Credit LineGift of Helga and Phil Fleishman

Object number2001.17

DepartmentJapanese Art

ClassificationsPainting

On View

Not on viewThis painting represents Yi Xing (Japanese: Ichigyo), a Chinese monk of the Tang dynasty and the fifth patriarch of the Esoteric school of Buddhism. Seated on a low platform chair, Yi Xing is depicted as a round-headed man with bright eyes and sturdy figure. Beneath his brown monk’s robe his hands are clasped before his chest.

Esoteric Buddhism was transmitted to Japan by the Japanese monk Kukai (774–835), who had studied in China for two years. After his return to Japan in 806, he established the Shingon sect of Buddhism. Shingon literally means "true word," meaning a sacred spell. Mystical rituals, gestures, and syllables as well as mandalas (sacred diagrams) were a key feature of Shingon Buddhism. These practices appealed to Japanese commoners who wanted to engage in a religious practice they believed would ward off evil.

According to Shingon practice, Esoteric doctrine is transmitted directly from masters to initiated disciples, giving great significance to the ceremony of initiation (kanjo). Portraits of the eight early patriarchs of Esoteric Buddhism were hung on the walls of temples, and incense was burned before them. By this means, disciples were informed of the lineage of transmission. As Shingon developed, more sets of portraits of the patriarchs were created, based on a small number of originals. The painter of this work probably copied Yi Xing’s features from those in earlier portraits.

Esoteric Buddhism was transmitted to Japan by the Japanese monk Kukai (774–835), who had studied in China for two years. After his return to Japan in 806, he established the Shingon sect of Buddhism. Shingon literally means "true word," meaning a sacred spell. Mystical rituals, gestures, and syllables as well as mandalas (sacred diagrams) were a key feature of Shingon Buddhism. These practices appealed to Japanese commoners who wanted to engage in a religious practice they believed would ward off evil.

According to Shingon practice, Esoteric doctrine is transmitted directly from masters to initiated disciples, giving great significance to the ceremony of initiation (kanjo). Portraits of the eight early patriarchs of Esoteric Buddhism were hung on the walls of temples, and incense was burned before them. By this means, disciples were informed of the lineage of transmission. As Shingon developed, more sets of portraits of the patriarchs were created, based on a small number of originals. The painter of this work probably copied Yi Xing’s features from those in earlier portraits.

Hanabusa Itchō

1709-1724

Chobunsai Eishi

![Zhongda [Sima Yi] Besieges Kongming [Zhuge Liang]](/internal/media/dispatcher/63368/thumbnail)