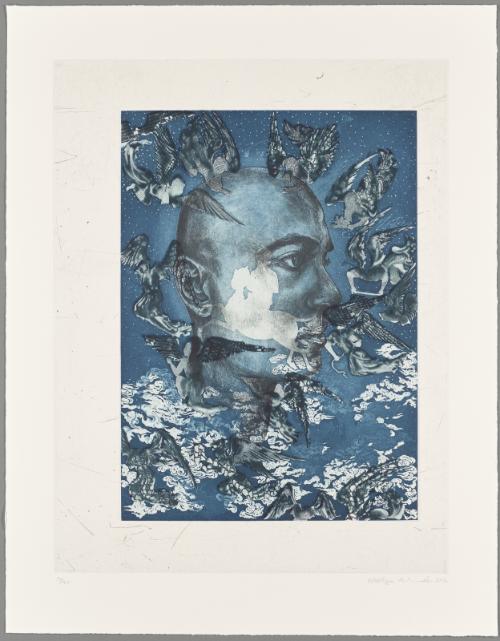

Portrait of the Artist

H. 27 x W. 21 1/4 in, H. 68.6 cm x W. 54 cm (overall)

A Journey into the Great Unknown

Et ignotas animum dimittit in artes.

[And he turned his mind to unknown arts.]

—Epigraph to A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by James Joyce

Making art is both exciting and intimidating. Shahzia Sikander, an artist who lives and works in New York, explored these two aspects of the creative process in a recent collaboration with the poet, playwright, and novelist Ayad Akhtar. In this suite of four etchings, entitled Portrait of the Artist in a nod to James Joyce, Sikander blends portraiture of herself and Akhtar with imagery related to the Mi’raj—the mystical night journey of the Prophet Muhammad from the Great Mosque in Mecca to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem and his ascension to heaven for an encounter with God. Variously interpreted as either a literal or metaphorical journey, the concept of the Mi’raj is a powerful theme in Islamic art and literature. For Sikander and Akhtar, this mystical journey becomes an important touchstone for artistic (re)imagination. Akhtar expresses this idea in his text:

For what else is Miraj if not the fulfillment of any artist’s deepest longing: to have made a journey into the great unknown— to have seen the unseeable—and to return to the world as we know it with the capacity to express the inexpressible?

Sikander draws on imagery from Central Asian, Persian, and Indian miniature painting in her art. These visual quotations, seen in the silhouetted white figure of Muhammad on the mythical winged creature Buraq and the Archangel Gabriel, and in the celestial beings (peris), are inspired by historical Mi’raj paintings in the collections of the British Library and the Topkapı Palace Museum. In addition to art historical allusions, Sikander’s imagery also makes reference to eminent literary sources. The illustrated manuscripts of the Khamsa by twelfth-century Persian poet Nizami, the fifteenth-century Persian Mi’rajnama, and Qur’anic literary traditions all play a role for Akhtar and Sikander, as do Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises (1926), and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by James Joyce (1916).

How is a Portrait Like a Poem?

About her collaboration on this work with the writer Ayad Akhtar, Shahzia Sikander writes:

An artist often has the burden to reimagine. In reimagining lies the ability to break molds and reexamine the norms. . . . A portrait to me is like a poem. It’s a reflection of a human emotion. . . . There are endless ways of imaging a human emotion. . . . Making a portrait of another is like playing the role of the detective, to look behind the mask, so to speak. In the Portrait of the Artist series, the “idea” of the artist is evoked, including the idea of the Prophet as artist.

In these four prints, Sikander explores a portrait of an artist as an exercise in exploring the eclectic cultural and artistic lineages that contribute to that artist’s voice. For Sikander and Akhtar, this involves thinking about art and representation in a contemporary American context. The accompanying text written by Akhtar explores not just the Mi’raj but also the calling of any artist and the particular conditions under which he and other Muslim artists currently work. On this topic he states, “To be a Muslim artist operating in the proverbial West means to work in a condition of impairment.”

Akhtar’s text, called a colophon by the two creative partners, defies easy characterization as a piece of writing—part poem, part history, part op-ed, and part journal entry, it memorializes this project as an “homage . . . to our own long, winding, yearning journeys.” It provokes the viewer to think about the innate human desire to create, and reminds us of the infinite possibilities of art to cross boundaries through time, among disciplines, and between people.

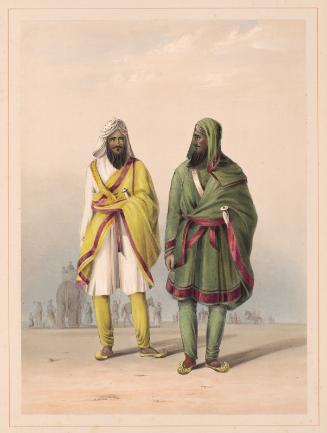

![[1] Young Student at the Hindu College in Calcutta, [2] A Child of One of the Servants of Government House](/internal/media/dispatcher/67726/thumbnail)